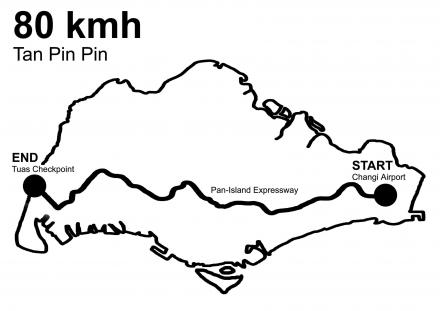

How long does it take to drive across Singapore at a constant speed of 80kmh?

I traverse the country in one long take. I start the camera rolling at an eastern point (the steeple of Changi Airport) and stop recording at a western point (Tuas Checkpoint). With no cuts, I document every inch of the country, from one exit point to the exit point at the other end of the island.

I keep the speed consistent at 80km/h so that this document has cartographical value. If the same route along the Pan Island Expressway is recorded every year, Singapore’s topographical changes can be mapped with previous recordings. I plan to film this road trip regularly.

This cross country document is a mere 38 minutes. Its duration is its message.

Recently, in the Aedes Gallery, Berlin, in an exhibition about WOHA Architects, the 2004 and 2005 versions were played side by side. We noticed that in one year, there were already many changes.

Screenings

- Singapore History Museum

- p-10

- Australian Film and Television School

- University of Technology Sydney

- Singapore Art Show

- Berlin House of World Cultures

- Institute of Contemporary Art, London

Credits

Conceived and shot by Tan Pin Pin

Titles by Mindwasabi

With help from, Isaiah Lim, Thio Lay Hoon, Suryahti Abdul Latiff, Lo Mun Hou, Jacqueline Loh, Irina Aristarkhova, Singapore Film Commission

Straits Times Review

by Emily Chua, Dec 5, 2004

Singapore’s fleeting past

Works by young Singaporean artists reflect a deep sense of loss

A SMALL island-nation whose government has been monopolised by the same political party since its inception, Singapore is a place whose history has largely been written in the single voice of the dominant authority.

It is therefore refreshing to find a group of young local artists who each appear to have, through their different artistic practices, all arrived at the question of their past.

A recent exhibition at an independent art space in Little India called p-10, And we took ourselves out of our hands (In Search of the Miraculous), featured several works that looked at Singapore’s past and raised questions about the nature of history itself.

For film-maker Tan Pin Pin, “Singapore jumped from Third World to First World in the years I grew up, the post-independence years of the 70s and 80s. Its development is nowhere more pronounced than in the speed in which buildings are demolished and built over. Growing up, I felt I was standing on soft ground.”

The product of this sentiment, Tan’s 80km/h, is a single-take video shot from the passenger’s seat of a car as it dissects the country at 80kmh along the Pan Island Expressway (PIE). A cartographic ritual henceforth to be repeated once every three years, Tan’s project promises to document the same cross-section of the country over a period of time.

In some ways, it is a piece that is already 30 years too late. A banal series of well-manicured trees, factories, schools, and block after block of government flats, 80km/h captures a Singapore that is unlikely to experience many more dramatic changes.

Yet it is perhaps in this lament that the piece works best. The artist’s desire to “obsessively document” originated in a developing Singapore that no longer exists.

Precisely because of this, the monotonous survey of the developed cityscape as it stands today serves only as an inadequate monument to all that is now irretrievably lost without a trace. Beyond Tan’s drive-by panorama, history exists as nothing but the individual’s imagination.

One way of dealing with the pain of this separation is suggested in Lee Sze-Chin’s Last Transmission. A video of the artist crying while watching Wit, an HBO original starring Emma Thompson, the piece stems from Lee’s desire to mourn the closing of Singapore’s first and only arts radio station, Passion 99.5 FM.

Caught without a video camera during the last moments of the station’s final broadcast, Lee missed capturing the actual event but decided afterwards to commemorate his sadness anyway, by using Wit as the substitute stimulant to move himself to tears.

A bizarre leap of logic, Last Transmission is compelling precisely in its pathetic determination to undertake the necessarily doomed enterprise of resurrecting a moment passed, in order to mark its passing.

Possessing a document of the past without the actual experience, on the other hand, is just as uncomfortable a situation as Guo Liang’s Greetings From An Old World describes.

Printed on a pamphlet that viewers can take home, the piece comprises a photograph of the 1930s’ Singapore amusement park, Happy World, and the artist’s reflections on the artefact.

“One imagines a place filled with street performers breathing fire and contortionists balancing china on their bent limbs; adrenaline- pumping joyrides and fantastical carousels,” the artist writes.

“Storytellers and fortune tellers line up side by side along narrow pathways and backside alleys, offering a concoction of old legends and mystic truths.”

This pointless exercise in fantasising about the past seems to be the artist’s almost involuntary, knee-jerk response to the image of a Singapore that came and went before him.

Yet after waxing lyrical for a couple of more paragraphs, even he cannot but realise the hollowness of his own initial response.

“I had reached the limit of the image and there was no way else to go. On hindsight, the image had never promised to take me anywhere other than the confines of its two-dimensional surface.”

Forsaking the stories that education and tradition have programmed us to repeat, the historical document, it seems, functions only as a reminder of the fundamental disconnect between the viewer and the past, an always misleading trace of a world whose truth must remain undiscovered, irrevocably sealed in the past.

Between one artist’s failed response to a historical document and two artists’ failed attempts to write them emerges a sense of documentation itself as the always frustrated desire to hold on to times that are constantly falling away.

Mere traces, documents leave the historian not with singular and objective truths about the past, but with subjective and incommunicable, imaginary reconstructions.

Radically undermining the view of history as a reproducible set of facts, the artists in this show experienced the past as that which is fundamentally and absolutely the no-longer-present.

What is realised between these three artworks is the quiet sadness surrounding every moment that passes the point of the present.

Emily Chua is a young Singaporean artist. Her collaborative works with Rutherford Chang were exhibited during SENI 2004 and at R(A): Rated Artistic at PKW gallery.