This interviewed by Joanne Leow appeared in Issue 88 of Senses of Cinema, published in October 2018. The interview itself was conducted in November the year before during a retrospective of my films at RIDM, Montreal.

Tan was born in 1969 in Singapore and was trained in law in the United Kingdom and in documentary filmmaking in the United States. Her experimental documentaries and award-winning short films have consistently evinced an awareness of the Singapore’s cramped and disciplined spatialities. Her first made for television documentary Moving House (2001), for instance, chronicles the exhumation of graves in Singapore driven by urban development and features a final haunting image of a columbarium filmed in a manner that makes it an undeniable visual echo of Singapore’s public housing flats. Her most recent film In Time To Come (2017) is a time capsule of the rituals, demolitions, and patterns in everyday Singaporean life. The film asks what is worth preserving in contemporary life.

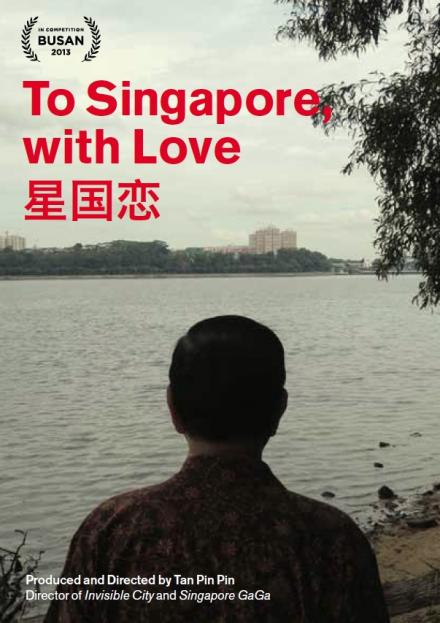

In between these two works, Tan has made over a dozen other documentaries and short films, the most famous and popular being Singapore GaGa which played to packed halls and theatres all over the island. The film is an aural record of the disappearing sounds of the island: busker songs that wind their way around our hearts, the cacophony of footsteps in an underpass, the specific hollow echoes of void decks and an eclectic range of songs that reflect the city’s polyglot, cosmopolitan, postcolonial nature. Her follow-up Invisible City (2007) is in her words, “a documentary about documenteurs,” “an ode” to all those who made Singapore the subject of their work. In this later film, she seeks to understand the impulse that drives these chroniclers, while bringing their lost histories to light. Her most controversial film, To Singapore, With Love (2013), was filmed entirely outside the country, documenting the emotionally constrained lives of political exiles from the country. The film was banned for public screenings in Singapore despite appeals by Tan and fellow filmmakers. She also filmed a short dramatic film, Pineapple Town, as part of the commissioned omnibus of Singapore films 7 Letters (2015) for the nation’s 50th anniversary.

By revealing the constructed and conditional aspects of Singapore’s history and spaces, Tan’s work allows us to depart not just from Singapore as mapped space but Singapore’s official history as mapped time. Tan’s directorial vision weaves alternative chronotopes of Singapore that are open-ended, frayed at the edges and still in the process of becoming. These revelations are often tied to the slow, contemplative pace of her films, her refusal to move quickly over the everyday, and the unpredictable or seemingly random aspects of her filmic space. Jini Kim Watson notes how Tan is profoundly conscious of the “highly formulaic elements… the militarized, productivist and multiculturalist logic… of the most disciplined and value-added workforces in the world.” [1]

Tan’s films’ polyphonies and digressions are particularly powerful for their eschewal of any grand narrative to describe a city-state whose government is singularly obsessed with its teleological progress. She does this with the full awareness that memory can never be complete, thorough, or exhaustive. Indeed, therein lies its power. This unmooring of memory from an official nationalism is echoed in the free associative rhythms of Tan’s films. The film’s desire for the past refuses a totalizing agenda, is not for profit, and does not pin Singapore or its inhabitants down. This indeterminacy makes memory open to the possibilities of other histories that challenge the singularity of the official history. These histories leave the film’s viewers open to a whole range of complex and nuanced meanings.

This interview was conducted in Montreal, Canada in November 2017 on the occasion of the Montreal International Documentary Festival’s retrospective of Tan’s entire oeuvre over four nights. This was the first time that all her films were shown in sequence, something that would not be possible in Singapore since the state has refused to issue a classification rating for To Singapore, with Love which effectively means it cannot have public screenings. In our conversation, Tan reflects on the body of her work, the politics of documentary filmmaking in Singapore, and her hopes for the country.

Joanne Leow: I think it’s really interesting that it’s only possible to see all your films together outside Singapore, here in Montreal, since To Singapore, with Love is banned there.

Tan Pin Pin: It’s interesting to see all these films consecutively actually. I just feel as if I’ve just started. I feel like I’ve just started and oh my goodness, it’s the wrong time to have a retrospective now.

JL: What are some of the through threads that you see in your work, though, now that you have the opportunity to review it in this retrospective?

TPP: I feel as if I am trying to conjure up ghosts. I see it Invisible City, To Singapore, with Love, and The Impossibility of Knowing. It’s as if I am trying to speak for, bring forth, bring notice to people events or places that can’t speak for themselves, which makes me a temple medium. And a medium should not just conjure up what is, a medium should conjure up what could be. And what we have lost, so it’s multidimensional. If it was entirely representational in a way that sometimes fiction is, I would be shortchanging the stories that I am trying to tell.

JL: it’s interesting to me because you are kind of venturing into the realm of speculative ideas. What do you do to make that apparent in a nonfictional documentary? How do you think you’re depicting things that could have been? What techniques do you usually go for to try and do that?

TPP: The wonderful thing about the cinematic medium is that it allows you to fill in the gaps yourself as a viewer. So much of great film is about the act of engaging the viewer in such a way so that the viewer is participating in the storytelling as well. I myself try to do it in different ways. For example in The Impossibility of Knowing, it was a direct attempt to push the limits of an image to see if a scene of trauma was filmed in provocative and film noir-ish ways, whether the traumas that had taken place in those places could be communicated to the viewer with just the address placed over the image. It didn’t quite work, so we added a voice over where Crimewatch [2] presenter, Lim Kay Tong reads the news reports of the accidents that happened in those locales. What you have is a still of the scene, and address appears and voice over comes on speaking of the tragedy that took place there.

In In Time to Come, we intercut scenes of daily rituals together, scenes like fire drills, morning assemblies, grand openings, to give an idea of timelessness in the sense that it is not clear when these films were shot. At a certain point, the film lifts into what could be perceived as a future Singapore, before it drifts back again to what appears to be the past. The time frame shifts through sound design and through editing.

In To Singapore, with Love, a film about Singapore political exiles, we made a very deliberate decision not to show any scenes of Singapore. The only scene we have of Singapore is of a very transitory space, the Singapore Changi airport. So from these views of exiles who have not been back to Singapore, some for more than 40 years, you had to conjure up an image of Singapore from their viewpoints, their descriptions of what they did, what they had done, why they had to leave, and their lives now, the viewer has to imagine the country today. My job as a director is to reduce information, while keeping the enquiry and curiosity of the viewer alive.

JL: What is really evocative for me is that poem Chan Sun Wing reads in To Singapore, with Love, where he names the places, he names the streets in Singapore. And obviously, those street names for him, embedded as they are in the past, they are so significant, each name means so much…

TPP: Yes, he names the places, very specifically. So does Ang Swee Chai when she says, “I want to be back at 100A Serangoon Road”, it is her Serangoon Road home of 40 years ago. Tan Wah Piow too gives a very specific address of his home in Joo Chiat. I could make another version of The Impossibility of Knowing, this time filming homes of Singapore political exiles, where they once lived, and where they are not able to return to. It would be an interesting portrait of their experience and of the country.

JL: Your work is concerned with an idea of time in a country where time is not only amnesiac but also very regulated. Not only in our everyday lives where we have the ordinary work day or migrant workers working around the clock, but also in the sense that in Singapore time is already mapped out and planned out for decades to come. For instance in the Master Plan, what do we want to achieve in 5, 10 or 30 years.

TPP: I think for In Time To Come that was exactly what I was trying to grapple with. One of the things that I filmed in In Time To Come was the morning assemblies. And when I first came across that morning assembly, one of the things I noticed was how unchanged it had been in the past 30 years since I was in school. You would never imagine that such a ritual would have been maintained for so long. But then it’s all related back to the fact that Singapore has been governed by the same political party for so many years. So the hierarchical format of the school assembly is of course just a direct analogy of how Singapore has been governed. And my idea was to show the sameness, the repetition and maybe to suggest the idea that we haven’t actually moved in spite of all of these changes. The same theme is covered in 9th August, a short film I made which mined 42 years of National Day Parade footage to show that camera angles for that bombastic annual event had not changed in all these years too.

JL: Saying that we haven’t changed is something quite radical, when we always think about progress. We’re moving forward!

TPP: Yes! We’re moving forward, we have terminal 4 now at Changi Airport, we have a new expressway. But what I am proposing through In Time to Come, is that we haven’t actually moved, nothing has changed. And so how do you translate that idea of nothing changing but everything changing at the same time? So you’re forward looking, you’re future looking, but you haven’t actually moved.

JL: I remember an earlier interview when you said that you didn’t want to make political films and if that has changed over the years, then what has changed in your thinking about being political? And can you think of a moment or a series of moments when it came to you that your filmmaking had changed or your purpose had changed?

TPP: I think the question of whether it is political or not is not the right question. Documentaries have always been read to be “more political” just by virtue of it being a documentary, than say fiction film. So whether I wanted it or not, just making a documentary, highlighting issues and showing Singapore as is, is already considered a political act in a country where not long ago, people were noticed for having views. In Singapore, being an artist can be a political gesture. Many of my films were made to find out how I feel about certain issues, and the audience follows me as I pursue a line of enquiry. I don’t start a project knowing the point I want to make. For To Singapore, with Love, making the film led me to question the shaky foundations of the ruling party, realising this and continuing with it was an important moment for me.

JL: Do you think that in course of 1996 to 2017 that your concerns and goals have changed? What are a couple of watershed moments that you felt compelled to film something or compelled to edit a particular way?

TPP: In 1995, while I was shooting Moving House (1996), I wanted to give up before the shoot because though I am not superstitious, I was freaked out at having to go to the Chinese cemetery in the middle of the night to cover the exhumation of a grave. Even with a crew, I was scared. I remember telling myself then, there was no one I could push this task to, it was either me, or this scene would not be filmed. But I wanted the exhumation of my great-grandparents grave documented for posterity, so I bit my lip and shot it. I remember feeling very resentful that I had to be the one to do it. Comical, when you think about it now.

When we are shooting, there is always the idea that what we are shooting may or may not end up in the screen because you can always drop the scene in the edit suite, so when I was shooting To Singapore, with Love, going around the world, interviewing Singaporean political exiles, I didn’t think much of what I was doing until I got into the edit room. There was a moment though, during a shoot at Changi Airport where I was to film Ho Juan Thai’s kids and wife arriving in Singapore, I had just flew in from Hat Yai and went straight the next terminal without a break. I was emotionally tired from the Thai trip and when I started shooting a grandmother [3] meeting her grandson for the first time, I just burst into tears.

So I thought, this has never happened before. Why was I crying? I was angry at the situation of Juan Thai being left in Johor Bahru while his mother met his sons in Changi. The application of the Internal Security Act had wreaked havoc in many families since Independence. Singaporeans needed to know about this. I continued to shoot, even though I felt shaky physically and emotionally.

JL: You’ve always said that you make films to satisfy your curiosity. But to make To Singapore, with Love was in some ways to satisfy everyone’s desire for a fuller accounting of that point in our history.

TPP: In the dark of the night, alone in the edit room, I was going through rushes and stumbled upon footage of Chan San Wing stoically reading the poem of him missing Singapore. By the end of the poem, I was sobbing, from the futility of his lot. They have been censored out of Singapore completely. I was also very aghast that the system could inspire so much fear in me. Fear of what? The proverbial midnight raids, incarceration, confiscation of cameras and computers that Singapore activists past and present had experienced. I asked myself if I wanted to cross the Rubicon and for whom this film was for.

JL: You decided to cross the Rubicon and many of us are very grateful.

TPP: I decided to cross the Rubicon because I felt I had no right to call myself a film director if with all the training that I’ve had, the scholarships that I was endowed with, if at this point, I was going to turn tail and not do what needed to be done. I could not hide the footage away and pretend it never happened.

Originally, I had wanted to take a more impressionistic and experimental film. In the end, I chose a more accessible form, consisting of talking head interviews with text and newspaper clippings filling in information whenever there were informational gaps that had to be addressed. This film was for my retired teacher aunty living in Siglap. Also, I felt that since the interviewees have been censored, I wanted to give them a platform to speak for themselves.

JL: What I find really interesting is not just the fact that it’s a film about political exiles, or being away, and that whole idea of displacement and history, that’s all very important and crucial to the narrative, but it was that you added that “with love.” What kind of love is expressed in the film? Sometimes it’s patriotic fervor, like with Ho Juan Thai, but there’s also love in Francis’s song, love in Chan San Wing’s poem. So how did your understanding of what the word “love” is in the national context change or come to mean something else after you completed it?

TPP: I have to say it was a tactical decision to name it that. Because I thought if you couch a potentially incendiary film with very soft words, it might kind of… you know, censors might not…

JL: Was that a little naïve on your part?

TPP: Yes, what was I thinking? Maybe I should have had a little plushie that came with the film as well, to temper the edge. For To Singapore, with Love, since the state archives from that period have not been released, I could not verify a lot of information from that period beyond first person accounts. However, the exiles still have strong feelings for Singapore, and they can talk about what they feel about Singapore, the circumstances of their escape without being accused of being inaccurate. So the film had a strong emotional undercurrent.

To answer your earlier question, this film tried to define “love” in a national context. The word is overused by propaganda committees to the extent that it has become meaningless to most people. But I wanted it addressed without sarcasm or irony. What does it mean to love your country? Who do these activists they speak for?

JL: You have spoken about how hard it was to see To Singapore, with Love banned, in Singapore, and to go through that process of not even being able to distribute it from the country. How do you think that will affect and has affected your filmmaking going forward? Or when you are looking for potential funding?

TPP: I don’t think I’ll be asked to direct the National Day Parade! My subsequent films were all commissioned before the ban so it’s hard for me to say where I might stand moving forward with regard to state support. But I have been making independent documentaries for over 20 years in Singapore. I have survived this long, using creative and lifestyle strategies developed in those years. I will continue to make work and keep an independent stance moving forward.

JL: What kinds of films do you think you would make without this uncertainty, without this unspoken context of what lines you can or cannot cross?

TPP: No, I’m not bound by any boundaries anymore, because as I said the watershed moment would be the making of To Singapore, with Love, because once you do something like that, all the emotional heavy lifting, in terms of the conversations you have with yourself about why you do what you do would already have been done. I would like to live outside Singapore for a period. A change of scenery would be good, to see if being in a less censorious regime can inspire other kinds of film.

JL: What kind of hope or vision do you have for Singaporean artistic community and Singaporean audiences in general? The ones who tried to see the film but couldn’t see the film, who may have secretly seen the film. But also the ones abroad, what hope do you have? What would you like to see?

TPP: Ideally this film would be taught in schools. It should be part of reading lists in social studies or Singaporean history. I want this film to inspire questions like what it means to be a citizen of a country or what is Singapore. Is there a role for civil disobedience or the Internal Security Act? A country is always in the state of becoming and allowing students to understand that their voices and actions can shape the country is important.

JL: To also have the younger generation have a chance to understand how the country was put together, the legacies of that communist period, the colonial powers…

TPP: Decisions that had to be made for better or worse. I would like them to consider the need for reconciliation, and how reconciliation can help the country moving forward.

JL: A kind of mature and public conversation about amnesty, about the return of exiles?

TPP: Yes, amnesty, what does it mean for the country and why it is important? The tone of the film was pitched at that frequency because I hoped it could start conversations. It could have been a lot more emotional. But I decidedly did not take that tone because I felt it would have closed the possibility of having this kind of conversation that gave both parties a chance to air their views. Alas, this olive branch was not taken up, they banned the film.

JL: You’ve always said in this and other films that you use the camera to get to know your subject better. What have you learned about Singapore and Singaporeans in the past two decades that might not have been so apparent to you, that was surprising to you? Or in some ways, represented something exceptional and unique in the way we go about living our lives in the kind of context that we are in?

TPP: For most people in the West, they don’t understand how Singaporeans can tahan [4] being Singaporeans. But didn’t you say anything when that happened? How can you just sit there? So why have my countrymen been seen to be so particularly docile in all these matters that seem so important to others? Is it because they don’t know about it? We have lost our voice and tragically, we don’t know it. We may not even know what it feels like to have one.

JL: I do think there is a certain level of ignorance. That basic “we don’t know”. I mean I didn’t know so many of the stories until you brought them to light.

TPP: Maybe the scarier version is that even though we know, we don’t care? Hence, I am always looking for moments of defiance, when people act up and rebel because they do. A lot of my films try to show that moment of defiance, that gleam in the eye. You see this in Singapore GaGa. Even in Invisible City you see these young archaeologists doing the backbreaking work of remembering.

JL: One of the things that I’ve learnt from your films is what defiance looks like in our context. It’s very different from defiance that we are accustomed to like loud protests or dramatic gestures but it’s in the everyday.

TPP: Right. There are little gestures of everyday resistance in every one of my films. In the final ceremony in Moving House, the affected family got a Taoist medium to apologise to their exhumed parents who were evicted from their gravesite to a columbarium, by saying they were required by the government to do it.

JL: Seen together then, what do you hope to leave behind with your body of work?

TPP: I would like to broaden the idea of what cinema can be in Singapore. That’s why I was intent that In Time To Come had to have a theatrical release in Singapore. And a lot of work goes into making a theatrical release despite the cost. We need to push the envelope of what Singaporeans get to see in a Cineplex, and people whom you don’t expect to go will get something out of the experience.

I want to broaden the idea of Singapore. Singapore is a work in progress and we all have a part to play in deciding what form it takes.

The author acknowledges that this interview was made possible by funding from the University of Saskatchewan.

Endnotes:

[1] Jini Kim Watson, “Aspirational City.” Interventions 18, no. 4 (July 3, 2016): p.547

[2] Crimewatch is a long running television series in Singapore that reenacts crime investigations.

[3] Referring to Ho Juan Thai’s mother.

[4] The Malay word for “endure.”

Photo Credit: Ulysse del Drago